This week’s New York Times speaks to the puzzler in all of us, and it explains how my addled brain* just may help me get from here to Christmas.

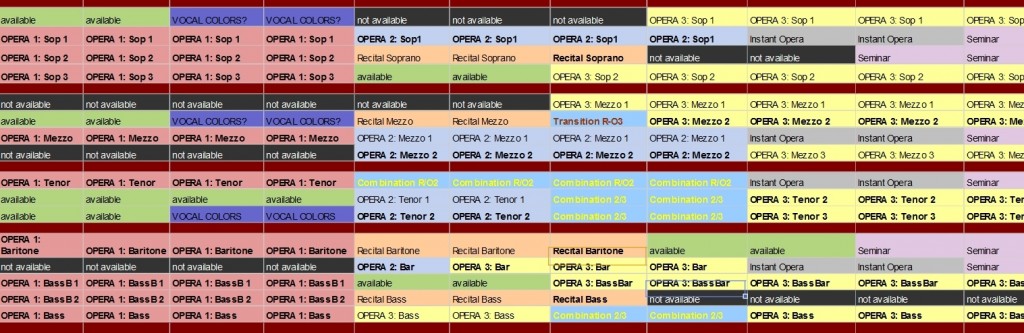

“Tracing the Spark of Creative Problem-Solving” is just the medicine I needed. Now that I know a positive mood can be responsible for “lowering the brain’s threshold for detecting weaker or more remote connections,” I have license to lighten up while I’m solving the recalcitrant December puzzle that is choose the singers / hurry up / choose the operas / make a calendar / should’ve been done yesterday / hire the staff / pay for it with a budget that was approved before we knew what any of it was. Oh, and do it in about 2.5 weeks.

Every year I look forward to coming home after our audition month on the road, conveniently forgetting that December is in its own way as much of a challenge. I’m not a happy puzzler by nature, with the exception of embarrassingly easy crosswords. So this exercise, while a happy one, makes me forget to breathe.

Most folks who want to go into arts administration crave being able to cast an opera. For good reason, too, for it’s an incredibly exciting and satisfying activity. As the Times article says, cracking any puzzle is all about creating order from chaos. “And once you have” (says Dr. Marcel Danesi of the University of Toronto), “you can sit back and say, ‘Hey, the rest of my life may be a disaster, but at least I have a solution.’ ” A well-crafted summer calendar is its own reward.

My whining is recreational, for as many of you know, we do things this way for a good reason. Choosing operas only after we check out each year’s applicant pool is an unparalleled way to craft a season around the folks who are out there. Careening into Christmas as Mrs. Grinch is a small price to pay.

* “Those whose brains show a particular signature of preparatory activity, one that is strongly correlated with positive moods, turn out to be more likely to solve the puzzles with sudden insight than with trial and error (the clues can be solved either way). This signature includes strong activation in a brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex. Previous research has found that cells in this area are active when people widen or narrow their attention — say, when they filter out distractions to concentrate on a difficult task, like listening for a voice in a noisy room. In this case of insight puzzle-solving, the brain seems to widen its attention, in effect making itself more open to distraction, to weaker connections.”

Add Comment