A Marriage of Figaro guest post from conductor Kathy Kelly

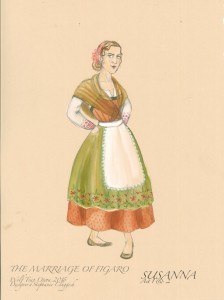

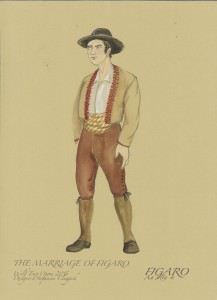

Act one, scene one: the chambermaid has just confessed to the manservant that, before they can marry, their lord and master intends to bed her. Just as they’ve worked through his angry and suspicious reaction to this news, she’s called away on an errand; they’ll have to steal a chance to talk later. “Coraggio, mio tesoro!” says Figaro as Susanna hurries away. “E tu, cervello!” she responds. “Courage, my love!” “And you, keep your wits about you!”

Act one, scene one: the chambermaid has just confessed to the manservant that, before they can marry, their lord and master intends to bed her. Just as they’ve worked through his angry and suspicious reaction to this news, she’s called away on an errand; they’ll have to steal a chance to talk later. “Coraggio, mio tesoro!” says Figaro as Susanna hurries away. “E tu, cervello!” she responds. “Courage, my love!” “And you, keep your wits about you!”

Faith in the power of reason and the courage to use it was boiling in the veins of Enlightenment-era Europeans. Vienna in 1786 was a conservative capital in major political and philosophical upheaval. Joseph II had succeeded his revered mother, the empress Maria Theresa, five years earlier, and had begun at once a series of remarkable reforms. He revamped the legal system, attempted in the face of heavy opposition to free the serfs, made education compulsory for boys and girls, instituted a firm policy of religious tolerance, and ended censorship of the theater. Most of these reforms would be reversed after his death, but the air of Vienna in the 1780s was charged with a spirit of optimism and possibility. In this atmosphere of reform, the emperor agreed that the poet of Vienna’s Italian theater, Lorenzo da Ponte, should make an operatic adaptation of Beaumarchais’ succès de scandale, Le mariage de Figaro. Mozart and Da Ponte probably began work on Le nozze di Figaro in summer 1785, scarcely a year after the play had delighted and shocked Paris.

If you know and love the opera, don’t miss the chance to read the original play. The Parisian Beaumarchais’ cynicism is nowhere to be found in Da Ponte’s libretto. But both works believe completely that happiness is possible through the power of logical minds, generous hearts, and courage of convictions. Individual disappointments are temporary, errant characters are brought back to balance through the loving wit of others, and new harmony seems possible.

Situations destabilize quickly when the inhabitants of Aguasfrescas dare to speak their minds, and we are privy to them working things out with combined reason and daring. Susanna takes the opera’s first dare when she tells Figaro about the Count’s plans: coraggio. Left alone, Figaro walks up to the edge of rage. “Sapró…sapró…ma piano!” he sings:

Situations destabilize quickly when the inhabitants of Aguasfrescas dare to speak their minds, and we are privy to them working things out with combined reason and daring. Susanna takes the opera’s first dare when she tells Figaro about the Count’s plans: coraggio. Left alone, Figaro walks up to the edge of rage. “Sapró…sapró…ma piano!” he sings:

“I’ll…I’ll…but wait!” No unthinking violence for him, but rather technique, skill, and patience. Cervello.

Figaro’s plan to entrap his employer involves Susanna, the Count’s wife, and the page Cherubino. The young page dares, when alone with the Countess, to confess his love to her. When the Count returns and Cherubino and Susanna are both hiding in the Countess’ chamber, we’re watching classic French bedroom farce. But Cherubino’s confession has charged the air, and the Countess is able to openly accuse her husband and give voice to her hurt and despair. When she returns after intermission, she’s revamped Figaro’s plan without his knowledge. In her remarkable aria “Dove sono”, she reflects again on the injustices of her husband’s behavior, but resolves that hope lies in her own constancy – her own coraggio.

Marcellina and Bartolo, friend and employer from Figaro’s days in Seville, show up at the estate. Figaro owes Marcellina money, and had promised to marry her if he couldn’t pay up. Now she’s taken the chance to hold him to his promise. This act threatens to torpedo everybody’s hopes, but ends up revealing the greatest surprise in the opera. On the off chance that you don’t know the story, I’m not going into any further detail, because it truly is a beautiful surprise! And it’s another example of someone shaking things up through their own daring, and that shakeup giving way to a world of greater harmony.

Marcellina and Bartolo, friend and employer from Figaro’s days in Seville, show up at the estate. Figaro owes Marcellina money, and had promised to marry her if he couldn’t pay up. Now she’s taken the chance to hold him to his promise. This act threatens to torpedo everybody’s hopes, but ends up revealing the greatest surprise in the opera. On the off chance that you don’t know the story, I’m not going into any further detail, because it truly is a beautiful surprise! And it’s another example of someone shaking things up through their own daring, and that shakeup giving way to a world of greater harmony.

What about the master of the house, our Count Almaviva? He thinks he should get what he wants simply because he is the master. “Vedró mentr’io sospiro felice un servo mio?” he asks – “should I watch my servant be happy when I am not?” All the wit and courage he has will go for nothing in such a small and selfish pursuit of happiness.  Caught by his household at the opera’s conclusion, he performs what is perhaps the day’s most profound act of courage: he asks his wife for forgiveness in a musical phrase of total simplicity. This “Contessa, perdono” often gets a laugh from the audience, which is disappointing (and even maddening) to those who feel worshipful about the music. But it’s an honest reaction, because the Count’s request is truly ridiculous. He doesn’t deserve to be forgiven. And yet, this man who has not acted with humility since the curtain went up sees that humility is his only choice, and the master gains the courage to kneel.

Caught by his household at the opera’s conclusion, he performs what is perhaps the day’s most profound act of courage: he asks his wife for forgiveness in a musical phrase of total simplicity. This “Contessa, perdono” often gets a laugh from the audience, which is disappointing (and even maddening) to those who feel worshipful about the music. But it’s an honest reaction, because the Count’s request is truly ridiculous. He doesn’t deserve to be forgiven. And yet, this man who has not acted with humility since the curtain went up sees that humility is his only choice, and the master gains the courage to kneel.

Coraggio e cervello, in the service of the most powerful amor.

All the rightful couples are restored to one another, and join in singing that only love could bring such a crazy day to its best conclusion. The revolutionary idea that all – master and servant, man and woman, young and old – are free to speak and act in their own interests will challenge the social order. And yet, at the end of the day, the household, the human community at its heart, is preserved.

Well said.