BY WILLIAM BERGER

You know the title character of Tosca, either personally or by hearsay. She’s opera’s version of that girl in school — the one they warn you about, whose company will cast doubt on your taste in friends. Yet everyone talks about her, and everyone wants something from her. No one ignores her, even if many denounce her baleful influence.

You know the title character of Tosca, either personally or by hearsay. She’s opera’s version of that girl in school — the one they warn you about, whose company will cast doubt on your taste in friends. Yet everyone talks about her, and everyone wants something from her. No one ignores her, even if many denounce her baleful influence.

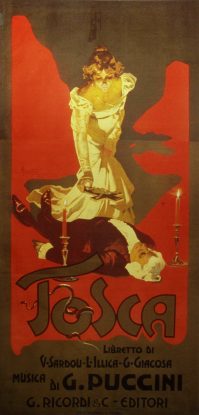

This tragedy is straightforward enough on the surface: The revolutionary painter Cavaradossi and his lover, the tempestuous diva Tosca, are in a life-and-death struggle with the evil police chief Scarpia, who wants to kill him and possess her, all of it unfolding in 12 hours starting on the afternoon of June 17th, 1800, during Napoleon’s invasion of Italy. The source is a play written for the legendary Sarah Bernhardt by Victorien Sardou in five acts and elaborately prepared with backstory and corroborative detail. Much of that Gallic reason is swept away in the Italian opera’s three acts, with protagonists clashing in spontaneous explosions, propelling the plot to its climax. It’s so effective that Sardou himself thought the trimming was an improvement over his own work.

There remains in Giacosa and Illica’s libretto the same copious supply of action, but presented in less time — and with less rational preparation on the part of the characters.

The opera contains a fugitive chase, a torture scene, an attempted rape, a murder, an execution, and a spectacular suicide — but much of the context hovers offstage: the radical, dangerous nature of artists, the French Revolution (the Queen of Naples who remains unseen in Act II is the sister of Marie Antoinette), the Napoleonic Wars, and so forth.

Puccini’s score was as lean and earthy as the libretto — from the loud, brash opening chords to the loud, brash chords at the end. The emotional impact is undeniable, if controversial. Some have found the opera manipulative and overwrought. Musicologist Joseph Kerman notoriously judged it a “shabby little shocker,” and composer Benjamin Britten called the score “sickening.” Reactions to the opera are sometimes more melodramatic than the opera itself. The frenzy goes beyond critics. Hugh Vickers’ Great Operatic Disasters, a classic trove of opera lore, cites Tosca as the supreme “bad luck” opera, a sort of operatic Macbeth (superstitious actors claim Shakespeare’s play is cursed). Vickers says that if your theater is going to burn to the ground, it will be during a performance of Tosca.

Yet Tosca is pure Puccini, exhibiting everywhere the indelible stamp of the maestro of operatic realism, the creator of memorable commoners like Mimì in La bohème and Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly. Tosca, too, is a real woman, as some of her greatest portrayers have discovered (commentator Ira Siff famously said that Maria Callas’ searing performance made him think he “was watching the events upon which the opera Tosca was based”). How can both the opera and the woman be at once real and supernatural?

We must remember the importance of setting to Puccini and his contemporaries: Paris in La bohème, Nagasaki in Madama Butterfly, and Gold Rush-era California in La fanciulla del West make the characters and situations in those operas possible and believable. But the city of Rome rules all, as it always does (being “Caput mundi,” the “head of the world”), and Rome itself is the reason Tosca reaches beyond melodrama to realism. The sites of each act (the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, the Palazzo Farnese, and the Castel Sant’Angelo/Hadrian’s Tomb) form a historical triad: Rome is the ancient world empire (which reached its largest extent under Hadrian), it is the bloody yet beautiful Renaissance city-state (the Farnese family was one of Cinquecento Rome’s most important and influential), and it is the place where God and his messengers directly intrude on human affairs (the namesake statue of the angel atop the Castel Sant’Angelo is a feature of most productions).

Rome is much else besides. It is queen of the arts, represented by erratic geniuses such as Caravaggio, whose name Cavaradossi’s suggests. It is the capital of the modern nation of Italy. It is the seat of the Church, which the bells at the beginning of Act III recall. (No visitor soon forgets the mighty campanone of Saint Peter’s, whose repeating low E becomes the bass pedal for Cavaradossi’s aria “E lucevan le stelle.”) Rome is also a labyrinth of secrets, with tunnels, hiding places, wells, dark garden paths, and torture chambers, the perfect setting for whispered Jesuit plots (indicated in an aside in Act II).

This real woman of Rome, then, is also a force of nature, a creature of myth (think of the equally intense Anna Magnani in the films Roma, città aperta or Mamma Roma). She is a diva in the original sense — literally, a goddess. Tosca embodies forces that she herself can barely contain: Her kiss is fatal (“Behold the kiss of Tosca!” she tells Scarpia, as she plunges the knife into his chest), like that of the biblical Salome, Dvořák’s Slavic water spirit Rusalka, and the Spider Woman of film and Broadway. She recalls the demon Lilith, the subject of a Sumerian hymn that tells us, “No mortal man could taste her kiss and live.” And in fact the only women we see Tosca interact with on stage are artistic depictions, the Madonna (in statuary form) and St. Mary Magdalene, the subject of Cavaradossi’s painting, both in Act I. The “realism” of Tosca lies in the truth that some women are much more than the girl next door. They are the centers of their own galaxies, radiating passion, devotion, and hatred and inspiring those in their orbit to do the same. They become embroiled in harrowing situations of gut-punching intensity. Is Tosca too much? Hardly. It’s a wonder it isn’t even more intense, brash, and over the top.

William Berger is a writer, producer, and radio commentator for the Metropolitan Opera, and a frequent lecturer on the arts and other subjects. He is the author of several books on opera, including Puccini Without Excuses by Vintage Books.